Schuldiger Realismus

In My Mold

Leah Barna, Antonia Alessia Virginia Beeskow, Bureau AEIOU, Andreas Cretin,

Jonas Höschl, Benni Kakert, Istihar Kalach, Christian Kölbl, Konstitutiv der Möglichkeiten, Jody Korbach, Marie Meyer, Max Sand, Nicolai Saur, Natalia Schwappacher,

Anica Seidel, Marta Vovk, Nicholas Warburg

curated by Julian Volz

GUILTY REALISM

I.

In fascist Germany in 1937, two communist resistance fighters discuss realism. While they agree that the merits of the French and Russian realists of the 19th century lie in the fact that with them the slaves, the parched, the impoverished became visible for the first time, they discuss the realisms of the 20th century in a much more controversial way. One resistance fighter is strictly on the party line and praises the achievements of socialist realism. Every worker understands the happy and victorious proletariat depicted there. The second is a bit more anarchistic and allows himself a heretical question: Doesn’t socialist realism, with its kitsch of the ideal world, remind one more of historical and allegorical images than of realistic art? Don’t the heroisations in its imagery just counteract the realistic character of these pictures? What can a realistic art in the age of fascism look like that does not simply paint a wishful image of reality?

II.

“It’s all about realism” was the tenor of a lively debate in the 1930s whose protagonists were a philosopher from Ludwigshafen and a former People’s Commissar of the Hungarian soviet republic. The one had a soft spot for the expressionist avant-gardes, in whose language he himself practised philosophy, while the other cultivated his preference for the bourgeois novel of the 19th century. Only in this novel was the objective truth of bourgeois society presented, in this novel the capitalist totality was revealed. The avant-gardes, on the other hand, had declared a subjectivist war on reality, according to the former People’s Commissar. The other retorts: In view of the rampant capitalist crisis processes, one could no longer speak of an objectively-closed reality at all: “The expressionists were ‘pioneers’ of decay: would it have been better if they had wanted to be doctors at the bedside of capitalism? If they had patched up the surface coherence instead of tearing it open further and further?”

III.

In the midst of thriving post-war welfare and warfare capitalism, some realist-oriented artists in the capitalist metropolises started a Taylorist organised production of artworks. They called their studios factories and organised happenings in furniture stores. The goods depicted in their paintings belong to the heart of the unrealism of real society. In one detail, the works of West German realism from the era of High Fordism differed from those of US realism. While the Yankee works revolve around products of mass consumption and mass culture, in the West Germans there is at least an inkling that the culture of post-Nazi Germany is not absorbed in them. So they also have other motifs, such as an alienated stag in the undergrowth or the Neuschwanstein Castle commissioned by King Ludwig II. Other materials, such as felt, are also used. There could not have been a more suitable exhibition venue for Capitalist Realism in West Germany than the Berges furniture store in Düsseldorf with its stuffy interiors. But at the latest with the crisis processes of 1973 and the implementation of neoliberalism, this idyll was over. To the extent that the commodity lost its use value, it was no longer suitable for its auratisation. Thus, this realism lost its historical raison d’être.

IV.

At the beginning of this millennium, a German performance artist set up several containers on a square in the centre of Vienna. Several asylum seekers moved into the containers for a week. In their everyday lives, they were filmed continuously by cameras - similar to reality TV. On top of one of the containers, the artist put up a banner with the words “Foreigners out”. In the morning, speeches by Jörg Haider were played over a loudspeaker and every evening a deportation took place. The audience was allowed to vote on which of the asylum seekers living in the container should be deported that day. The action aroused the passions of the Viennese population. There were tumultuous scenes in front of the container day and night. Anti-fascist activists organised a counter-demonstration and tore down the “Ausländer Raus” sign, while other passers-by were very happy about the deportations. Shortly before, the right-wing FPÖ had been elected to the Austrian government. The cultural policy spokesperson of the FPÖ strongly condemned the action. She said it falsely placed Austria in a right-wing corner.

V.

A universal formula of what is meant by realism is difficult to establish. I will suggest that realism is characterised neither by a particular form nor by a particular content. It is not a style, but a method. An artistic method of knowing social reality and at the same time a method of political intervention. What a realist method is, however, can only be concretely determined historically.

VI.

For a realism of the present, the substantive question now arises as to the social reality of the current epoch. Are we, for example, in the midst of a period of fascisation heading towards a third world war or are we living in the era of uprisings and the death crisis of capitalism? And the question then arises in which artistic forms this social analysis can be expressed. What form can an image of reality take today?

In the age of (post-)postmodernism, of post-late zombie capitalism, it is difficult to speak of a closed, recognisable reality. So the question is rather how the surface context can be further torn open and what can be brought to light in the process. If it is true that the term National Socialist Underground does not only refer to a three-headed gang of murderers, but rather sums up Germany’s collective unconscious quite accurately, then one can expect a lot when tearing open this surface. The artists gathered in this exhibition were not too shy for this work: they show what nationalist, racist and (neo-)fascist thinking and acting is present in Germany and Europe today, process it in their art and make the unease about it clearly perceptible. In doing so, they conspicuously follow an approach by Brecht, who once wrote: “Historically significant (typical) are people and events that may not be the most common or most eye-catching on average, but which are decisive for the developmental processes of society. The selection of the typical must be made according to what is positive (desirable) for us as well as according to what is negative (undesirable).” Brecht also said, “Realism does not leave it at ugliness [...] by presenting ugliness as a social phenomenon.”

Now, of course, it is politically harmless to turn to the positive with one’s art, because that automatically puts one on the right side. The artists in this exhibition have chosen a different approach: For them, the undesirable seems to have gained such dominance in our present that it is not enough to simply look the other way and make feel-good art oriented towards the left-liberal consensus that practices innocence. In the synopsis, a common form of aesthetics becomes clearly recognisable: the artists usually appropriate something typically German. This can take place on the material level, for example when they work with beer brands, baseball bats or wood, or on the level of motifs and content, which can be based on German myths and icons. The appropriated material is then reshaped and refracted using various strategies. Some works go so far as to appropriate (neo-)fascist aesthetics. While the New Right has been playing with leftist codes and forms of action for a long time, the reverse movement is riskier. The artists are obviously walking a fine line with their work: if the artistic treatment and refraction of the source material is not successful, their work can easily tip over into an affirmation of nationalist to fascist aesthetics. They consciously take the risk in their play with ambivalence, they make themselves guilty in the process. I therefore want to propose the term Guilty Realism for this form of art production.

VII.

Originally, Tannhäuser is a folk ballad about how the Pope refuses forgiveness to a sinner. Richard Wagner took the subject for his famous romantic opera Tannhäuser from Heinrich Heine, with whom he was initially friends and towards whom he later developed an anti-Semitic paranoia. So here we already find the motif of guilt, the adaptations of the Tannhäuser theme by progressive and reactionary artists and, last but not least, a very German-sounding word. The “circle” again evokes a conspiratorial aura. It suggests closeness, intimacy or mysticism, as in the George circle. The Tannhäuser Circle is the avant-garde of Guilty Realism.

VIII.

I hereby declare this cult of guilt to be definitively over.

Text by Julian Volz

Single Works

Exhibition Views

Schuldiger Realismus

In My Mold

Leah Barna, Antonia Alessia Virginia Beeskow, Bureau AEIOU, Andreas Cretin,

Jonas Höschl, Benni Kakert, Istihar Kalach, Christian Kölbl, Konstitutiv der Möglichkeiten, Jody Korbach, Marie Meyer, Max Sand, Nicolai Saur, Natalia Schwappacher,

Anica Seidel, Marta Vovk, Nicholas Warburg

curated by Julian Volz

GUILTY REALISM

I.

In fascist Germany in 1937, two communist resistance fighters discuss realism. While they agree that the merits of the French and Russian realists of the 19th century lie in the fact that with them the slaves, the parched, the impoverished became visible for the first time, they discuss the realisms of the 20th century in a much more controversial way. One resistance fighter is strictly on the party line and praises the achievements of socialist realism. Every worker understands the happy and victorious proletariat depicted there. The second is a bit more anarchistic and allows himself a heretical question: Doesn’t socialist realism, with its kitsch of the ideal world, remind one more of historical and allegorical images than of realistic art? Don’t the heroisations in its imagery just counteract the realistic character of these pictures? What can a realistic art in the age of fascism look like that does not simply paint a wishful image of reality?

II.

“It’s all about realism” was the tenor of a lively debate in the 1930s whose protagonists were a philosopher from Ludwigshafen and a former People’s Commissar of the Hungarian soviet republic. The one had a soft spot for the expressionist avant-gardes, in whose language he himself practised philosophy, while the other cultivated his preference for the bourgeois novel of the 19th century. Only in this novel was the objective truth of bourgeois society presented, in this novel the capitalist totality was revealed. The avant-gardes, on the other hand, had declared a subjectivist war on reality, according to the former People’s Commissar. The other retorts: In view of the rampant capitalist crisis processes, one could no longer speak of an objectively-closed reality at all: “The expressionists were ‘pioneers’ of decay: would it have been better if they had wanted to be doctors at the bedside of capitalism? If they had patched up the surface coherence instead of tearing it open further and further?”

III.

In the midst of thriving post-war welfare and warfare capitalism, some realist-oriented artists in the capitalist metropolises started a Taylorist organised production of artworks. They called their studios factories and organised happenings in furniture stores. The goods depicted in their paintings belong to the heart of the unrealism of real society. In one detail, the works of West German realism from the era of High Fordism differed from those of US realism. While the Yankee works revolve around products of mass consumption and mass culture, in the West Germans there is at least an inkling that the culture of post-Nazi Germany is not absorbed in them. So they also have other motifs, such as an alienated stag in the undergrowth or the Neuschwanstein Castle commissioned by King Ludwig II. Other materials, such as felt, are also used. There could not have been a more suitable exhibition venue for Capitalist Realism in West Germany than the Berges furniture store in Düsseldorf with its stuffy interiors. But at the latest with the crisis processes of 1973 and the implementation of neoliberalism, this idyll was over. To the extent that the commodity lost its use value, it was no longer suitable for its auratisation. Thus, this realism lost its historical raison d’être.

IV.

At the beginning of this millennium, a German performance artist set up several containers on a square in the centre of Vienna. Several asylum seekers moved into the containers for a week. In their everyday lives, they were filmed continuously by cameras - similar to reality TV. On top of one of the containers, the artist put up a banner with the words “Foreigners out”. In the morning, speeches by Jörg Haider were played over a loudspeaker and every evening a deportation took place. The audience was allowed to vote on which of the asylum seekers living in the container should be deported that day. The action aroused the passions of the Viennese population. There were tumultuous scenes in front of the container day and night. Anti-fascist activists organised a counter-demonstration and tore down the “Ausländer Raus” sign, while other passers-by were very happy about the deportations. Shortly before, the right-wing FPÖ had been elected to the Austrian government. The cultural policy spokesperson of the FPÖ strongly condemned the action. She said it falsely placed Austria in a right-wing corner.

V.

A universal formula of what is meant by realism is difficult to establish. I will suggest that realism is characterised neither by a particular form nor by a particular content. It is not a style, but a method. An artistic method of knowing social reality and at the same time a method of political intervention. What a realist method is, however, can only be concretely determined historically.

VI.

For a realism of the present, the substantive question now arises as to the social reality of the current epoch. Are we, for example, in the midst of a period of fascisation heading towards a third world war or are we living in the era of uprisings and the death crisis of capitalism? And the question then arises in which artistic forms this social analysis can be expressed. What form can an image of reality take today?

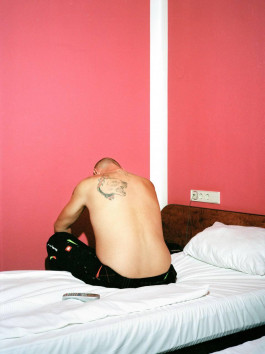

In the age of (post-)postmodernism, of post-late zombie capitalism, it is difficult to speak of a closed, recognisable reality. So the question is rather how the surface context can be further torn open and what can be brought to light in the process. If it is true that the term National Socialist Underground does not only refer to a three-headed gang of murderers, but rather sums up Germany’s collective unconscious quite accurately, then one can expect a lot when tearing open this surface. The artists gathered in this exhibition were not too shy for this work: they show what nationalist, racist and (neo-)fascist thinking and acting is present in Germany and Europe today, process it in their art and make the unease about it clearly perceptible. In doing so, they conspicuously follow an approach by Brecht, who once wrote: “Historically significant (typical) are people and events that may not be the most common or most eye-catching on average, but which are decisive for the developmental processes of society. The selection of the typical must be made according to what is positive (desirable) for us as well as according to what is negative (undesirable).” Brecht also said, “Realism does not leave it at ugliness [...] by presenting ugliness as a social phenomenon.”

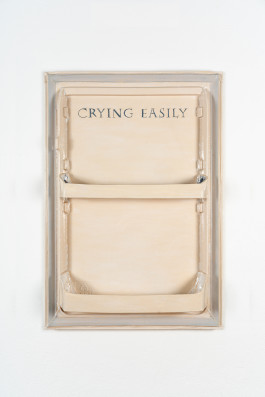

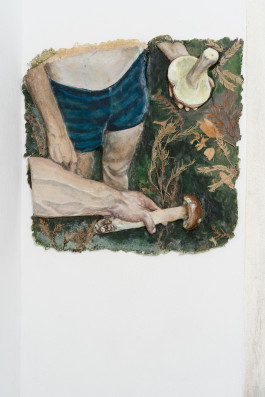

Now, of course, it is politically harmless to turn to the positive with one’s art, because that automatically puts one on the right side. The artists in this exhibition have chosen a different approach: For them, the undesirable seems to have gained such dominance in our present that it is not enough to simply look the other way and make feel-good art oriented towards the left-liberal consensus that practices innocence. In the synopsis, a common form of aesthetics becomes clearly recognisable: the artists usually appropriate something typically German. This can take place on the material level, for example when they work with beer brands, baseball bats or wood, or on the level of motifs and content, which can be based on German myths and icons. The appropriated material is then reshaped and refracted using various strategies. Some works go so far as to appropriate (neo-)fascist aesthetics. While the New Right has been playing with leftist codes and forms of action for a long time, the reverse movement is riskier. The artists are obviously walking a fine line with their work: if the artistic treatment and refraction of the source material is not successful, their work can easily tip over into an affirmation of nationalist to fascist aesthetics. They consciously take the risk in their play with ambivalence, they make themselves guilty in the process. I therefore want to propose the term Guilty Realism for this form of art production.

VII.

Originally, Tannhäuser is a folk ballad about how the Pope refuses forgiveness to a sinner. Richard Wagner took the subject for his famous romantic opera Tannhäuser from Heinrich Heine, with whom he was initially friends and towards whom he later developed an anti-Semitic paranoia. So here we already find the motif of guilt, the adaptations of the Tannhäuser theme by progressive and reactionary artists and, last but not least, a very German-sounding word. The “circle” again evokes a conspiratorial aura. It suggests closeness, intimacy or mysticism, as in the George circle. The Tannhäuser Circle is the avant-garde of Guilty Realism.

VIII.

I hereby declare this cult of guilt to be definitively over.

Text by Julian Volz

Single Works