Nicholas Warburg

Graduating Slytherin

06.12 - 07.02.20/21

On Graduating Slytherin

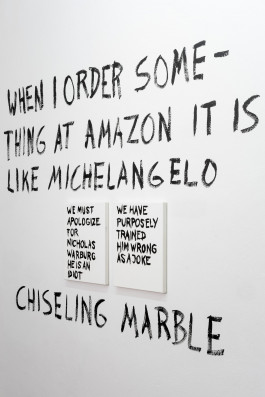

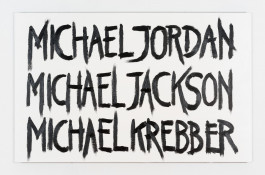

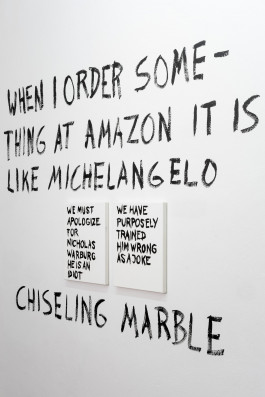

Nicholas Warburg completed his studies at the Städelschule in October 2020. Since no academic degrees are awarded there, he painted himself a diploma for his graduate exhibition - in the style of Slytherin, the house of the evil witchcraft and wizardry students in the Harry Potter novels. In his exhibition “Graduating Slytherin”, Warburg combines an ironic swan song of farewell to the myth of the Städelschule with the artistic procedure of Hauntology - a “nostalgia for lost futures”. The Städelschule avoids making itself dependent on institutional regulations. According to the faculty’s self-conception, the freedom of students and teachers is valued higher than an official degree. Last but not least, the Frankfurt School of Art is internationally known for its laissez-faire attitude. It is therefore diametrically opposite to e.g. US-American study programs. Seventy percent of the students at the Städelschule come from abroad. It is the only art school in Germany where English is the lingua franca. Yet with only 150 art students, it is also one of the smallest. Just under a thousand interested people apply for thirty openings each year. This was not always the case. The school’s rise from a rather non-profile provincial institution to international renown began in the late 1980s with Kasper König’s directorate and continued under Daniel Birnbaum and others. The teaching staff included and still includes Thomas Bayrle, Hermann Nitsch, Jörg Immendorf, Isabelle Graw, Wolfgang Tillmans, Douglas Gordon, Peter Fischli and Judith Hopf. Artists* such as Gerhard Richter, Isa Genzken, Martin Kippenberger, and Jason Rhoades have had shorter guest appearances as teachers. Well-known graduates include Tobias Rehrberger and Haegue Yang (both teach at the Städelschule today), Thomas Zipp, Danh Vō, Matias Faldbakken, Nora Schultz, Simon Denny, Anne Imhof, Lena Henke and Hannah Levy. But as in every institution, there is not only the official narrative of incisive milestones, big names and merits, but also the oral history of colportage: the stories of heroin in the student restrooms; of the scabies infestation at the school, the spread of which brought flings to light; of high school-like hierarchies among students (which forbade those with low social status to address those with higher); and of professors who held their classes exclusively in pubs. That was a long time ago, of course. Today everything is more dignified, more correct and perhaps a bit more boring. The hierarchy among the students is less manifest, a certain amount of self-sufficiency and toxic flair has remained. It is not for nothing that the Städelschule in Frankfurt, like most art schools in their respective cities, is considered a haven of arrogance. It has also earned the affectionate name Slytherin from other art students in Germany. Among the characteristics of the Slytherin student body are cunning and ambition. The Städelschule is viewed as a flow heater for art market careers - with all the necessary side effects: Competitive pressure, envy and the crippling fear of doing something wrong, which lies in the air with every end of year exhibition. In his exhibition “Graduating Slytherin”, Nicholas Warburg takes a look at the myth of the Städelschule as an inand outsider. It’s never quite sure whether the staging of his own persona is the product of his own narcissism or a commentary on art students in general or students of the Städelschule in particular. Among other works, his diploma painted in oil on canvas, a self-portrait as Marcel Proust, or the cover picture 5: “WE MUST APOLOGIZE FOR NICHOLAS WARBURG/ HE IS AN IDIOT/ WE TRAINED HIM WRONG/ AS A JOKE” speak of this self-referentiality. While Warburg had playfully addressed the 1950s to the 1980s in an exhibition at Anton Janizewski’s in 2019 under the title BRDigung, references to the 1980s to 2010s can now be found, analogous to the more recent history of the Städelschule.

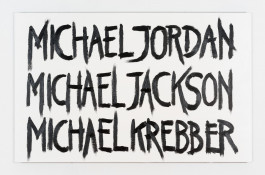

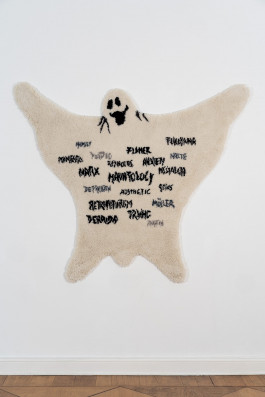

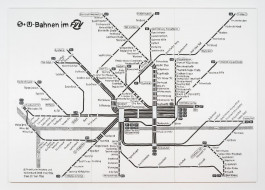

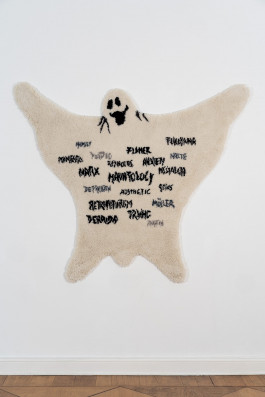

This is the case in two sculptural works: a stack of towels with a hundred mark banknote print lying on the floor, forming an oversized bundle of banknotes; and a pair of vintage 70s sunglasses, as they were fashionable again in the 90s, with the design of a 1 DM coin engraved in their lenses. One of the more political works (Geisterbahn) depicts the map of Frankfurt’s public transportation network from 1986 in oil on canvas and its full size, as it hangs in the track bed of the subway stations. It refers to a “Past That Will Not Pass” - the title of Ernst Nolte’s revisionist speech, which was printed in 1986 in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung and launched the Historikerstreit (Historians’ Dispute). Nolte had planned to give his speech in the Paulskirche, wich he was denied, however. There, twelve years later, Martin Walser was able to receive the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade and, in his speech, spoke of the Berlin Holocaust Memorial as a “monumentalization of shame”. In 2017, the Thuringian AfD leader Björn Höcke revisited this figure of speech and declared that the Germans were “the only nation in the world that has planted a monument of shame in the heart of its capital.” In the 1920s, the art and cultural studies scholar Aby Warburg (there is no relation to Nicholas Warburg) examined the persistence of imagery since antiquity, through the Renaissance, and into the present. According to Georges Didi-Hubermann, Aby Warburg follows the “phantom character” of pictures, which enables them to make spooky returns. This interpretation approaches the field of hauntology. The term was coined by Jaques Derrida and in more recent years was made fruitful by Mark Fisher, in particular, to describe the return of 1980s aesthetics in current pop music. But couldn’t a “nostalgia for lost futures” also be thought of in relation to the “1000-year Reich” and its haunting return in the present, to a past that wants to haunt us? On a hand-tufted tapestry in the outlines of a ghost from the TV series Scooby-Doo, Nicholas Warburg collects central names and terms from the hauntological cosmos in the aesthetics of a word cloud. On a two-meter wide canvas it reads: “MICHAEL JORDAN/ MICHAEL JACKSON/ MICHAEL KREBBER”. The typeface as well is based on the horror genre. The three protagonists named were born around the same time. While Michael Jordan and Michael Jackson were the greatest stars in their disciplines of all time, Michael Krebber is a different kind of celebrity. He is considered an artists’ artist, an eternal insider tip. He studied painting in Karlsruhe, was assistant to Georg Baselitz and Martin Kippenberger and from 2002 to 2016 professor at the Städelschule. His formal gestures and conceptual tricks often exceed the understanding of art experts. In many cases it remains unclear, for example, whether his refusal to produce is due to a lack of ideas or a deliberate bluff. His dandyish approach finds a resounding echo in Warburg’s exhibition. For instance, an empty display case placed in front of the central window of the gallery. Warburg comments laconically that he often feels an urgent need to look out of the window while visiting museums. This need, however, goes hand in hand with a guilty conscience regarding the exhibited art. With this work (The Outside), he allows the viewer to look at art and look out of the window simultaneously. One might think of Immanuel Kant’s “thing in itself”, which we cannot objectively perceive, but only comprehend what it appears to be for us individually. The totality of these appearances would be the Outside: ultimately as constructed and fragile and fleeting as art? Or does the Outside, when viewed through the glass of the showcase, become art, as it were? A work relating to this idea is “book recommendations from Isabelle Graw”, an oak corner shelf displaying a biography of Siegfried Kracauer, Angelika Klüsendorf’s novel “Years Later” and Merlin Carpenter’s still sealed essay “The Outside can’t go outside”. With the display case and shelf, Warburg seems to hint to the “lazy art” of the end of year exhibition of the Städelschule (“a few roof battens leaning against the wall”), as well as to risk a rather large conceptual leap or tear it down again, right away: AS A JOKE

Press:

Exhibtion Views

Nicholas Warburg

Graduating Slytherin

06.12 - 07.02.20/21

On Graduating Slytherin

Nicholas Warburg completed his studies at the Städelschule in October 2020. Since no academic degrees are awarded there, he painted himself a diploma for his graduate exhibition - in the style of Slytherin, the house of the evil witchcraft and wizardry students in the Harry Potter novels. In his exhibition “Graduating Slytherin”, Warburg combines an ironic swan song of farewell to the myth of the Städelschule with the artistic procedure of Hauntology - a “nostalgia for lost futures”. The Städelschule avoids making itself dependent on institutional regulations. According to the faculty’s self-conception, the freedom of students and teachers is valued higher than an official degree. Last but not least, the Frankfurt School of Art is internationally known for its laissez-faire attitude. It is therefore diametrically opposite to e.g. US-American study programs. Seventy percent of the students at the Städelschule come from abroad. It is the only art school in Germany where English is the lingua franca. Yet with only 150 art students, it is also one of the smallest. Just under a thousand interested people apply for thirty openings each year. This was not always the case. The school’s rise from a rather non-profile provincial institution to international renown began in the late 1980s with Kasper König’s directorate and continued under Daniel Birnbaum and others. The teaching staff included and still includes Thomas Bayrle, Hermann Nitsch, Jörg Immendorf, Isabelle Graw, Wolfgang Tillmans, Douglas Gordon, Peter Fischli and Judith Hopf. Artists* such as Gerhard Richter, Isa Genzken, Martin Kippenberger, and Jason Rhoades have had shorter guest appearances as teachers. Well-known graduates include Tobias Rehrberger and Haegue Yang (both teach at the Städelschule today), Thomas Zipp, Danh Vō, Matias Faldbakken, Nora Schultz, Simon Denny, Anne Imhof, Lena Henke and Hannah Levy. But as in every institution, there is not only the official narrative of incisive milestones, big names and merits, but also the oral history of colportage: the stories of heroin in the student restrooms; of the scabies infestation at the school, the spread of which brought flings to light; of high school-like hierarchies among students (which forbade those with low social status to address those with higher); and of professors who held their classes exclusively in pubs. That was a long time ago, of course. Today everything is more dignified, more correct and perhaps a bit more boring. The hierarchy among the students is less manifest, a certain amount of self-sufficiency and toxic flair has remained. It is not for nothing that the Städelschule in Frankfurt, like most art schools in their respective cities, is considered a haven of arrogance. It has also earned the affectionate name Slytherin from other art students in Germany. Among the characteristics of the Slytherin student body are cunning and ambition. The Städelschule is viewed as a flow heater for art market careers - with all the necessary side effects: Competitive pressure, envy and the crippling fear of doing something wrong, which lies in the air with every end of year exhibition. In his exhibition “Graduating Slytherin”, Nicholas Warburg takes a look at the myth of the Städelschule as an inand outsider. It’s never quite sure whether the staging of his own persona is the product of his own narcissism or a commentary on art students in general or students of the Städelschule in particular. Among other works, his diploma painted in oil on canvas, a self-portrait as Marcel Proust, or the cover picture 5: “WE MUST APOLOGIZE FOR NICHOLAS WARBURG/ HE IS AN IDIOT/ WE TRAINED HIM WRONG/ AS A JOKE” speak of this self-referentiality. While Warburg had playfully addressed the 1950s to the 1980s in an exhibition at Anton Janizewski’s in 2019 under the title BRDigung, references to the 1980s to 2010s can now be found, analogous to the more recent history of the Städelschule.

Exhibtion Views

Anton Janizewski Galerie,

Anton Janizewski Galerie,