Justin Chance,

Mona Filleul,

Monika Grabuschnigg

In My Mold

In My Mold

curated by Miriam Bettin

Under the title In My Mold the three person exhibition at Galerie Anton Janizewski, curated by Miriam Bettin, brings together new works by Justin Chance, Mona Filleul, and Monika Grabuschnigg. Their mainly sculptural practices based on the everyday are characterized by processes of molding and/or modifying/covering objects of daily use. Familiar yet alien things are combined in unexpected ways to create uncanny feelings. In this dialectical process, the works reveal the immanent political dimension of the personal.

The exhibition title does not only refer to the artistic practices but is also a description of a (not solely human) condition in which one cannot get out of one’s own skin or, in the broader literal sense, is stuck in mold.

All the more emphasized through the heavily ornamented art nouveau architecture of the gallery space, the works on display circle around the thin line and the tipping point between celebration, intimacy, seduction, and the morbid, grotesque, and melancholic of the everyday and the private realm. Following Juliane Rebentisch and her thoughts on critical melancholia, the feeling of melancholia is caused through a lost object whereby the object can be a person, an idea, an identity, a mode of living. The objects in the exhibition are distanced and partly lost because covered, blurred, alienated, or animated. Appealing at first, they turn out to be traps or cul-de-sacs, revealing their eerie banality that can easily turn into danger. Ultimately, the understanding of finitude has the productive potential to open up diverse perspectives of possibility and change.

Justin Chance, working in various media with a strong focus on textile, has slightly adapted and extended the traditional way of quilt making with his own set of rules – almost like following a linguistic system (assembling letters and fibres). Text and textiles have not only the same word origin, but also the power to narrate and to distribute stories: Especially quilts with their long history of Black and queer storytelling and empowerment, i.e. Faith Ringgold and her story quilts or the AIDS Quilt memorial in the 1980s and 1990s in Washington DC.

In Chance’s work, the middle part from figuratively needle felted wool on top of the base from cotton is covered and blurred by a transparent, permeable silk skin. The quilt’s principle of three layers and the in between, hold together by stitches, can be understood as a counter narrative to binary systems. „Nostalgic for the future“, Chance is interested in the gaps of life, death, and everything in between. The title Dying (2020/2021) refers to both literal meanings – in a craft sense to the dying of his own fibres, in a symbolic one to the end of life. The picture plane shows a spiraling tree with apples, highly loaded iconographic symbol, sin in paradise, poisened fruit in fairy tales.

Next to it, the standing fan (A English Rose, 2018) covered in carpet-like piled wool refuses to follow his very nature (to give air). Instead it turns restlessly in two directions, neither impressed by its surrounding nor the audience. The same applies to the train to nowhere (Long Distance, 2018), coated with skin-like latex, wax, special effects make-up, doing its rounds.

Far across the distance

And spaces between us

You have come to show you go on

Mona Filleul’s bas-reliefs from beeswax and papers out of mulberry fibers refer to yet another ancient craft technique, that of Japanese papermaking, that the artist ultimately turns into her very own practice. The motifs are taken from pop music culture and Filleul’s smartphone image archive of everyday life, however, always revealing only small, but often recurring details: Dinosaurus & Oranges Carrefour (2020) for example, a diptych, shows a man’s arm in a coat sleeve holding a shopping net filled with oranges, seen here as a vague simulacrum. Restrained in materiality and color, the vulnerable and downright uncomfortable immediacy of the imagery is all the more emphasized through the work’s plasticity, the skin-like organic materiality, and hyperfiguration, especially those partly painted with tempera and oil.

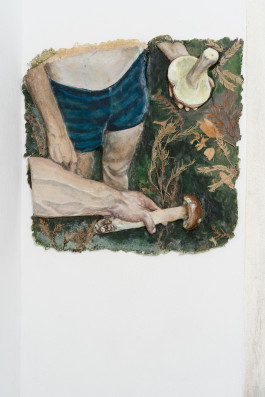

Objects from the personal realm (beauty accessories next to tools) as well as body parts (limbs, an exposed neck) open up public questions of relations, identity, and belonging. Time and again, materials from the so-called real life mix into the compositions such as dried plants on a hike through the woods next to vulgarly explicit mushroom representations (Eupen, 2021). Added to the six-part relief les costumes d’autres sur soi (2020-2022) with a painted magazine cover next to an eyeshadow palette, a razor, and anti-shaving-rush-balm, are found feminine-read clothes, hanging disembodied as on clothes racks waiting to be filled with life.

On ne change pas

On met juste les costumes d’autres sur soi

In her sculptural practice Monika Grabuschnigg mainly works with ceramic. With their shiny, seemingly perfect glazed surfaces, her works oscillate between digital language, industrial reproduction and organic craft. While translating domesticated and commodified objects into clay (clothing, wheels, body parts, plants), sometimes in real life size, other times blown up in scale, Grabuschnigg quotes from pop culture, philosophy, iconography, and psychology. With a tendency towards dark romanticism, Grabuschnigg’s sculptures and drawings portray and conserve a transient beauty and point to existential questions about life and death.

Her ceramic sculptures (Nightshade 5 and 6, 2022) are depicting enlarged berries of the deadly nightshade. The plant’s botanical name Atropa Belladonna refers to the Greek goddess of providence Atropos, who holds the thread of life in her hands. Historically, the fruit was used in medicine, as a tincture for beauty purposes or as a magic growth to get in touch with the afterlife – an Alice-like gateway to another world. This duality of seduction and threat raises awareness of one’s own transience and a forlorn sense of belonging to a larger whole.

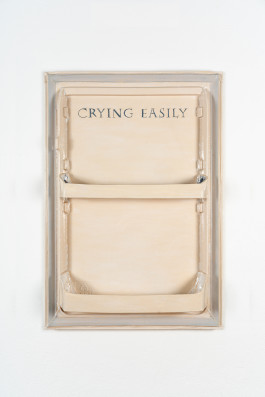

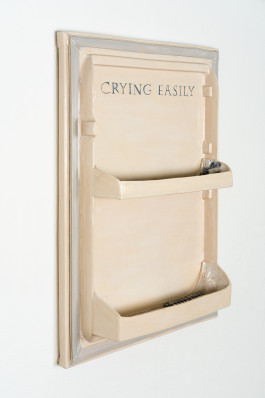

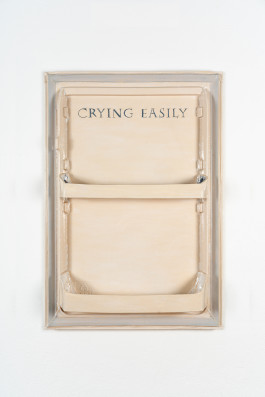

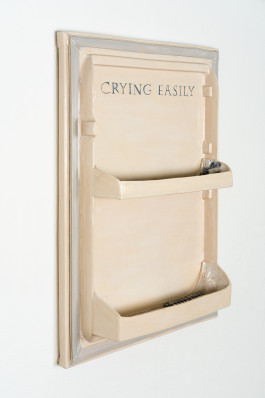

The ceramic reliefs Single Fridge (Crying Easily), Single Fridge (Ashtrays) and Single Fridge (Tomorrow breaks our gaze), all 2022, represent aspects of loneliness and isolation, as well as cravings towards an emancipated, unfolded self. Based on casts of the inside of fridge doors, they hang on the wall like framed tableaus, engraved with written confessions, decorated with the utensils of daily life. Aluminium-cast eye-drop vials and an empty tray for eggs evoke a sense of melancholia. Headstone ornaments, fragments of song lyrics, and other emotionally charged symbols are recurring motifs in Grabuschnigg’s work. The drawings of bouquets of drying flowers, the epitome of memento mori, comment on their own impermanence and fleeting moments of mourning.

A last look in the ribboned mirror (Justin Chance, Right Now, 2021) – a realization of the present self.

But I’m here in my mold

I am here in my mold

Text: Miriam Bettin

Single Works

Justin Chance,

Mona Filleul,

Monika Grabuschnigg

In My Mold

In My Mold

curated by Miriam Bettin

Under the title In My Mold the three person exhibition at Galerie Anton Janizewski, curated by Miriam Bettin, brings together new works by Justin Chance, Mona Filleul, and Monika Grabuschnigg. Their mainly sculptural practices based on the everyday are characterized by processes of molding and/or modifying/covering objects of daily use. Familiar yet alien things are combined in unexpected ways to create uncanny feelings. In this dialectical process, the works reveal the immanent political dimension of the personal.

The exhibition title does not only refer to the artistic practices but is also a description of a (not solely human) condition in which one cannot get out of one’s own skin or, in the broader literal sense, is stuck in mold.

All the more emphasized through the heavily ornamented art nouveau architecture of the gallery space, the works on display circle around the thin line and the tipping point between celebration, intimacy, seduction, and the morbid, grotesque, and melancholic of the everyday and the private realm. Following Juliane Rebentisch and her thoughts on critical melancholia, the feeling of melancholia is caused through a lost object whereby the object can be a person, an idea, an identity, a mode of living. The objects in the exhibition are distanced and partly lost because covered, blurred, alienated, or animated. Appealing at first, they turn out to be traps or cul-de-sacs, revealing their eerie banality that can easily turn into danger. Ultimately, the understanding of finitude has the productive potential to open up diverse perspectives of possibility and change.

Justin Chance, working in various media with a strong focus on textile, has slightly adapted and extended the traditional way of quilt making with his own set of rules – almost like following a linguistic system (assembling letters and fibres). Text and textiles have not only the same word origin, but also the power to narrate and to distribute stories: Especially quilts with their long history of Black and queer storytelling and empowerment, i.e. Faith Ringgold and her story quilts or the AIDS Quilt memorial in the 1980s and 1990s in Washington DC.

In Chance’s work, the middle part from figuratively needle felted wool on top of the base from cotton is covered and blurred by a transparent, permeable silk skin. The quilt’s principle of three layers and the in between, hold together by stitches, can be understood as a counter narrative to binary systems. „Nostalgic for the future“, Chance is interested in the gaps of life, death, and everything in between. The title Dying (2020/2021) refers to both literal meanings – in a craft sense to the dying of his own fibres, in a symbolic one to the end of life. The picture plane shows a spiraling tree with apples, highly loaded iconographic symbol, sin in paradise, poisened fruit in fairy tales.

Next to it, the standing fan (A English Rose, 2018) covered in carpet-like piled wool refuses to follow his very nature (to give air). Instead it turns restlessly in two directions, neither impressed by its surrounding nor the audience. The same applies to the train to nowhere (Long Distance, 2018), coated with skin-like latex, wax, special effects make-up, doing its rounds.

Far across the distance

And spaces between us

You have come to show you go on

Mona Filleul’s bas-reliefs from beeswax and papers out of mulberry fibers refer to yet another ancient craft technique, that of Japanese papermaking, that the artist ultimately turns into her very own practice. The motifs are taken from pop music culture and Filleul’s smartphone image archive of everyday life, however, always revealing only small, but often recurring details: Dinosaurus & Oranges Carrefour (2020) for example, a diptych, shows a man’s arm in a coat sleeve holding a shopping net filled with oranges, seen here as a vague simulacrum. Restrained in materiality and color, the vulnerable and downright uncomfortable immediacy of the imagery is all the more emphasized through the work’s plasticity, the skin-like organic materiality, and hyperfiguration, especially those partly painted with tempera and oil.

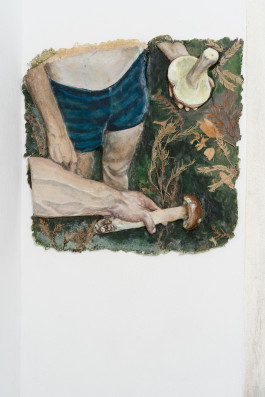

Objects from the personal realm (beauty accessories next to tools) as well as body parts (limbs, an exposed neck) open up public questions of relations, identity, and belonging. Time and again, materials from the so-called real life mix into the compositions such as dried plants on a hike through the woods next to vulgarly explicit mushroom representations (Eupen, 2021). Added to the six-part relief les costumes d’autres sur soi (2020-2022) with a painted magazine cover next to an eyeshadow palette, a razor, and anti-shaving-rush-balm, are found feminine-read clothes, hanging disembodied as on clothes racks waiting to be filled with life.

On ne change pas

On met juste les costumes d’autres sur soi

In her sculptural practice Monika Grabuschnigg mainly works with ceramic. With their shiny, seemingly perfect glazed surfaces, her works oscillate between digital language, industrial reproduction and organic craft. While translating domesticated and commodified objects into clay (clothing, wheels, body parts, plants), sometimes in real life size, other times blown up in scale, Grabuschnigg quotes from pop culture, philosophy, iconography, and psychology. With a tendency towards dark romanticism, Grabuschnigg’s sculptures and drawings portray and conserve a transient beauty and point to existential questions about life and death.

Her ceramic sculptures (Nightshade 5 and 6, 2022) are depicting enlarged berries of the deadly nightshade. The plant’s botanical name Atropa Belladonna refers to the Greek goddess of providence Atropos, who holds the thread of life in her hands. Historically, the fruit was used in medicine, as a tincture for beauty purposes or as a magic growth to get in touch with the afterlife – an Alice-like gateway to another world. This duality of seduction and threat raises awareness of one’s own transience and a forlorn sense of belonging to a larger whole.

The ceramic reliefs Single Fridge (Crying Easily), Single Fridge (Ashtrays) and Single Fridge (Tomorrow breaks our gaze), all 2022, represent aspects of loneliness and isolation, as well as cravings towards an emancipated, unfolded self. Based on casts of the inside of fridge doors, they hang on the wall like framed tableaus, engraved with written confessions, decorated with the utensils of daily life. Aluminium-cast eye-drop vials and an empty tray for eggs evoke a sense of melancholia. Headstone ornaments, fragments of song lyrics, and other emotionally charged symbols are recurring motifs in Grabuschnigg’s work. The drawings of bouquets of drying flowers, the epitome of memento mori, comment on their own impermanence and fleeting moments of mourning.

A last look in the ribboned mirror (Justin Chance, Right Now, 2021) – a realization of the present self.

But I’m here in my mold

I am here in my mold

Text: Miriam Bettin

Single Works

Anton Janizewski Galerie,