Zuzanna Czebatul

Jonas Höschl

Ahmet Öğüt

Gentle Reminder

13.04. – 20.05.23

On Gentle Reminder

If Höschl’s work deals with the invisible and the barely visible, then Zuzanna Czebatul’s pieces assert their presence in the gallery space with an almost excessive visibility. Her large sculpture Probably a Robbery (2021), made from polystyrene and acrylic plaster, is almost too tall for the space. It depicts two female figures, the fragment of a pilaster, and an arch.

A myth is neither a lie nor an assertion, but it transforms and bends sense into a form, writes Roland Barthes in his essay collection on the pervasiveness of myths in popular culture, until nothing of the content remains. Strangely, and precisely because of this, myths can claim universal validity. Myths have many names. Ideology, fiction, perhaps even fake news. They have an oblique way of being apolitical—and yet, they hold potential for politics, as the works in this show assert.

All three artists in Gentle Reminder deal with different aspects of this conundrum: nations and other fictions that have real consequences for the lives of people, patriarchy’s longstanding claims to power, or the insignia of extremist groups. Myths seem depoliticised, but traces of their political use are everywhere.

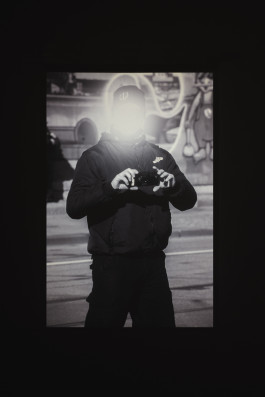

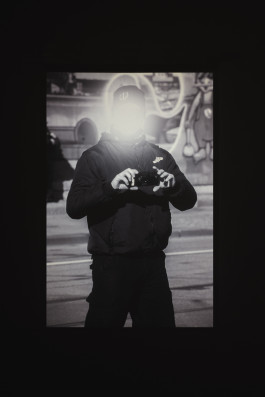

For this exhibition, Jonas Höschl shows three works. The latest is called 80 Portraits: 73 Männer, 7 Frauen, and it consists of a carousel slide projector, a device which recalls quaint nostalgic activities such as looking at vacation snaps. This one, however, runs through black-and-white photos, all depicting people in the same portrait format. Some of the poses are menacing, while the faces have been blurred out. The signifiers that these figures wear on their body—tattoos, shirts, logos, but also suits and folkloristic German apparel—betray their allegiance to far right groups. Höschl has sourced the images online, from anti-fascist networks where they have a clear purpose: mapping the Neonazi scene, documenting its protagonists, and potentially warning people who might fall victim to violent attacks. In the current setup, the pictures are lifted not only from their context, but also deprived of their function. They call to attention the mediated nature of photography: usually, photographer and subject are at considerable distance from each other, and only in rare cases the look is reciprocated, when the antifascists themselves are being photographed.

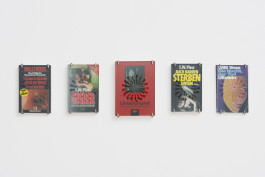

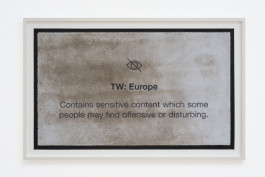

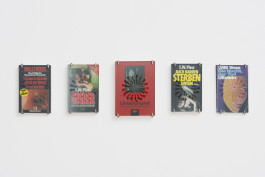

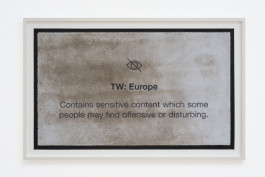

The pervasiveness of far-right ideology is also exemplified in another work, Tränen schützen nicht vor Mord (2022), named after a novel by E.W. Pless, aka Willy Voss, aka Willy Pohl. Before the author wrote genre fiction, he was, in the 1970s, part of a Neonazi underground network, worked as a spy, and he provided arms to the PLO terrorists who murdered the members of the Israeli olympic team in Munich in 1972. Höschl presents five of his novels behind glass, onto which he printed the 1972 logo for the Olympic Games, which incidentally resembles a Black Sun (a fascist symbol) or a bullet hole. The last work is a dirty doormat, initially presented in the show TW: Europe. TW is short for trigger warning, and visitors of that show had to step over that doormat emblazoned with the trigger warning pictogram one might see on Instagram, when explicit content is blurred out. Cross the threshold at your own peril. The figures are two caryatides from a façade in the Cour Carré of the Louvre.

High up and situated just below the central tympanum, they have an ornamental function, but when reproduced, details, such as the way they tenderly hold hands, become immediately visible. The artist had a 3D scan of the sculptures made, which itself is a kind of appropriation. This is linked to the history of the museum that transformed from a medieval keep into a suite of renaissance palaces, until, under Napoleon’s reign it became the receptacle for robbed artworks it is to this day. Czebatul is interested in bringing into view the human body, and especially the female body in a classicist context. The discourse about displaced artefacts is usually thought to be only about objects, but patriarchy and imperialism assert their power by referring to a classical canon and objectifying bodies as mere ornament.

The other work Czebatul presents is Gentle Reminder (of the Banality of Power) (2016), which lends the exhibition its title, a more playful take on a similar topic. It makes use of an ancient Roman technique of creating rondos and other ornaments, the opus sectile, for which segments of material are inserted into walls. Czebatul employs concrete and pigments to create colorful rondos that depict erect phalli. As the title suggests, it is a very literal reminder of where the power resides, but it also pokes fun at a patriarchal order.

Ahmet Öğüt takes on a different aspect of fiction. He presents two works that deal with the oppressive nature of nationhood. One is a part of the installation Stones to Throw, which first has been realised in Lisbon in 2011. The piece happened in two locations simultaneously, in Portugal and in Öğüt’s hometown, Diyarbakır. One part consisted of plinths, arranged in a grid, on each of which the artist placed a rock. The rocks were painted in the style of military aircraft, as it has been done since World War I: some with cartoonish toothy grins, others with characters lifted from comic books. Every few days, a courier would come and pick up one of the rocks to have them shipped to Diyarbakır in south-east Anatolia. The city has a Kurdish majority, and since the 1990s, conflicts between police, military, and protesting civilians have broken out. Young people and children face oppression by the Turkish forces, and they are frequently arrested for throwing stones. Öğüt’s painted rocks have been left in the roads of Diyarbakır, to connect the art space and public space and as an anonymous public intervention. Eventually, only one stone was left, after the work slowly disappeared in one place and appeared somewhere else.

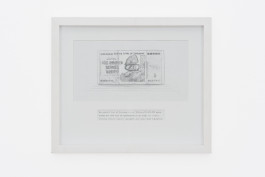

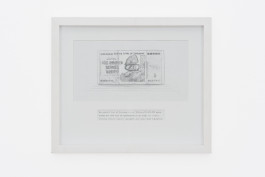

The two drawings that accompany the installation are part of the series Fantasized Fantastic Corporeal World (2019), which consists of eight drawings supplemented by brief typewritten texts, which provide more details on the sketches: a two-storey building, which operated as a fake US embassy in Ghana over ten years, issuing fake visas, for instance. Another is a bank note over one hundred trillion dollars, issued by the Bank of Zimbabwe in times of inflation. The works in this series are united in the way their backstories sound like fiction, but they are based on real occurrences, as if sometimes the fictions around nationhood are veiled only thinly. On a more conceptual level, however, the pieces share an interest in the imagined borders that restrict the movement of people, and they destabilise the boundary between fiction and the factual world.

Philipp Hindahl

Exhibtion Views

Zuzanna Czebatul

Jonas Höschl

Ahmet Öğüt

Gentle Reminder

13.04. – 20.05.23

On Gentle Reminder

If Höschl’s work deals with the invisible and the barely visible, then Zuzanna Czebatul’s pieces assert their presence in the gallery space with an almost excessive visibility. Her large sculpture Probably a Robbery (2021), made from polystyrene and acrylic plaster, is almost too tall for the space. It depicts two female figures, the fragment of a pilaster, and an arch.

A myth is neither a lie nor an assertion, but it transforms and bends sense into a form, writes Roland Barthes in his essay collection on the pervasiveness of myths in popular culture, until nothing of the content remains. Strangely, and precisely because of this, myths can claim universal validity. Myths have many names. Ideology, fiction, perhaps even fake news. They have an oblique way of being apolitical—and yet, they hold potential for politics, as the works in this show assert.

All three artists in Gentle Reminder deal with different aspects of this conundrum: nations and other fictions that have real consequences for the lives of people, patriarchy’s longstanding claims to power, or the insignia of extremist groups. Myths seem depoliticised, but traces of their political use are everywhere.

For this exhibition, Jonas Höschl shows three works. The latest is called 80 Portraits: 73 Männer, 7 Frauen, and it consists of a carousel slide projector, a device which recalls quaint nostalgic activities such as looking at vacation snaps. This one, however, runs through black-and-white photos, all depicting people in the same portrait format. Some of the poses are menacing, while the faces have been blurred out. The signifiers that these figures wear on their body—tattoos, shirts, logos, but also suits and folkloristic German apparel—betray their allegiance to far right groups. Höschl has sourced the images online, from anti-fascist networks where they have a clear purpose: mapping the Neonazi scene, documenting its protagonists, and potentially warning people who might fall victim to violent attacks. In the current setup, the pictures are lifted not only from their context, but also deprived of their function. They call to attention the mediated nature of photography: usually, photographer and subject are at considerable distance from each other, and only in rare cases the look is reciprocated, when the antifascists themselves are being photographed.

The pervasiveness of far-right ideology is also exemplified in another work, Tränen schützen nicht vor Mord (2022), named after a novel by E.W. Pless, aka Willy Voss, aka Willy Pohl. Before the author wrote genre fiction, he was, in the 1970s, part of a Neonazi underground network, worked as a spy, and he provided arms to the PLO terrorists who murdered the members of the Israeli olympic team in Munich in 1972. Höschl presents five of his novels behind glass, onto which he printed the 1972 logo for the Olympic Games, which incidentally resembles a Black Sun (a fascist symbol) or a bullet hole. The last work is a dirty doormat, initially presented in the show TW: Europe. TW is short for trigger warning, and visitors of that show had to step over that doormat emblazoned with the trigger warning pictogram one might see on Instagram, when explicit content is blurred out. Cross the threshold at your own peril. The figures are two caryatides from a façade in the Cour Carré of the Louvre.

High up and situated just below the central tympanum, they have an ornamental function, but when reproduced, details, such as the way they tenderly hold hands, become immediately visible. The artist had a 3D scan of the sculptures made, which itself is a kind of appropriation. This is linked to the history of the museum that transformed from a medieval keep into a suite of renaissance palaces, until, under Napoleon’s reign it became the receptacle for robbed artworks it is to this day. Czebatul is interested in bringing into view the human body, and especially the female body in a classicist context. The discourse about displaced artefacts is usually thought to be only about objects, but patriarchy and imperialism assert their power by referring to a classical canon and objectifying bodies as mere ornament.

The other work Czebatul presents is Gentle Reminder (of the Banality of Power) (2016), which lends the exhibition its title, a more playful take on a similar topic. It makes use of an ancient Roman technique of creating rondos and other ornaments, the opus sectile, for which segments of material are inserted into walls. Czebatul employs concrete and pigments to create colorful rondos that depict erect phalli. As the title suggests, it is a very literal reminder of where the power resides, but it also pokes fun at a patriarchal order.

Ahmet Öğüt takes on a different aspect of fiction. He presents two works that deal with the oppressive nature of nationhood. One is a part of the installation Stones to Throw, which first has been realised in Lisbon in 2011. The piece happened in two locations simultaneously, in Portugal and in Öğüt’s hometown, Diyarbakır. One part consisted of plinths, arranged in a grid, on each of which the artist placed a rock. The rocks were painted in the style of military aircraft, as it has been done since World War I: some with cartoonish toothy grins, others with characters lifted from comic books. Every few days, a courier would come and pick up one of the rocks to have them shipped to Diyarbakır in south-east Anatolia. The city has a Kurdish majority, and since the 1990s, conflicts between police, military, and protesting civilians have broken out. Young people and children face oppression by the Turkish forces, and they are frequently arrested for throwing stones. Öğüt’s painted rocks have been left in the roads of Diyarbakır, to connect the art space and public space and as an anonymous public intervention. Eventually, only one stone was left, after the work slowly disappeared in one place and appeared somewhere else.

The two drawings that accompany the installation are part of the series Fantasized Fantastic Corporeal World (2019), which consists of eight drawings supplemented by brief typewritten texts, which provide more details on the sketches: a two-storey building, which operated as a fake US embassy in Ghana over ten years, issuing fake visas, for instance. Another is a bank note over one hundred trillion dollars, issued by the Bank of Zimbabwe in times of inflation. The works in this series are united in the way their backstories sound like fiction, but they are based on real occurrences, as if sometimes the fictions around nationhood are veiled only thinly. On a more conceptual level, however, the pieces share an interest in the imagined borders that restrict the movement of people, and they destabilise the boundary between fiction and the factual world.

Philipp Hindahl

Exhibtion Views