Ferdinand Dölberg

Am Ende die Leerstelle

03.06. – 08.07.23

On Am Ende die Leerstelle

"La mort est du domaine de la foi" / "Death belongs to the domain of faith". - Jacques Lacan

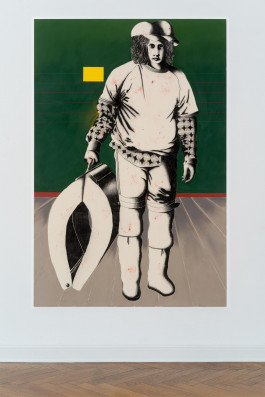

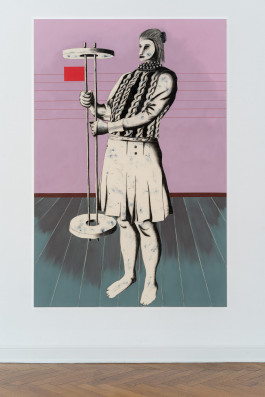

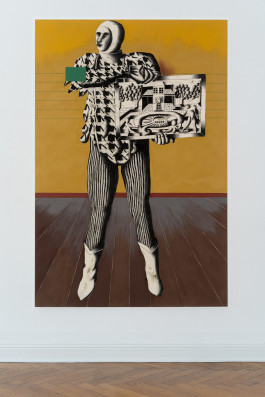

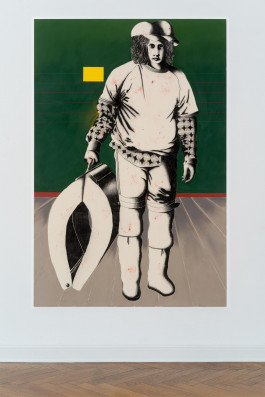

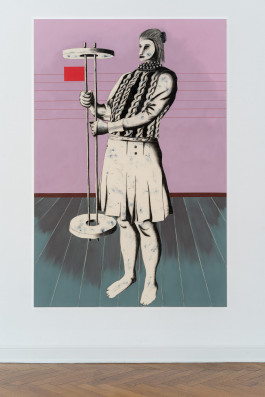

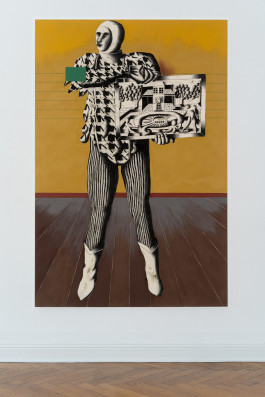

On the other side Reflections on Ferdinand Dölberg's "In the End, the Empty Space“ by Olga Hohmann. "La mort est du domaine de la foi" / "Death belongs to the domain of faith". Jacques Lacan When little children want to hide, they cover their eyes. They think that if they cannot see what surrounds them, they would themselves also be invisible to their surrounding. At some point, the moment will come when they realize that they remain visible, even if they cannot see what they are surrounded by. When they want to hide, they now look for a place where they actually cannot be spotted - they no longer close their eyes to do so. Perhaps this happens at about the same time that they reach Lacan's mirror stage: they now recognize themselves in the mirror and at the same time misrecognize themselves, perceiving themselves as a subject, as a closed entity. When people grow old and prepare, very slowly, to pass away, they sometimes experience something similar to children covering their eyes so as not to be seen. I remember my grandfather repeating over and over again that he was afraid of his death because we, the relatives, would then also disappear. "If I am no longer there, then you are no longer there either" he repeated over and over again. So death was also a logic problem for him - he imagined it as an "other side" from which we who were alive would be just as invisible to him as he was to us. In Ferdinand Dölberg's exhibition "Am Ende die Leerstelle" ("At the End, the Empty Space"), death is quite literally negotiated as another side: The property of the artist's deceased father borders on a cemetery; only a fence separates the area of flourishing life, the garden, from that of death, the equally flourishing gravesites. A ladder leans against the fence, one can use it to dare a look at the other side or even climb over it. The view of the cemetery is also a view into one's (own) future. Only since he has changed sides, so to speak, does the artist use this ladder to pay his father a visit. In Ferdinand Dölberg's portrait series we see those who have remained on the other side - they almost seem like apparitions, as if they carry a part of the soul of their deceased loved ones with them. They hold objects in their hands, mundane artifacts left behind by the deceased: A chalice, an umbrella, a heat lamp, a hand truck, a bouquet of flowers. Sometimes they are ephemeral objects - they too become sacred without seeming specifically religious; one can draw conclusions about the characteristics of the people who have passed away. The mourners all have their own form of spirituality, one believes to recognize them in their sharp, serious look. One can impute to them melancholy and emptiness as well as serenity. Slightly larger than life, they look down on us, the viewers, evoking the presence of the deceased with their devotion to them, almost looking as if they themselves are in heaven or at least in a limbo between life and death, an approximation of that, unreachable other side. They have climbed the ladder to look, with an almost matter-offact gaze, over the fence where (invisibly) the dead lie. The figures seem deeper, more three-dimensional than their background, than the (virtual) space they are in, they remain black and white, out of time, their background is monochrome, like a deck of playing cards.

One almost thinks the portrayed are game characters or avatars - the game, the loss, is serious. As mourners, they find themselves in an interstice between one world and the other; with their memories, they themselves establish the presence of the ones who are absent, who also remain present in the objects left behind. The colorfulness gives the paintings something slightly nostalgic - nostalgia is a longing for a state that was never there, just as the memory of the deceased is always a displaced one, shaped by those who remember. Objects become shields against the helplessness of pain - at the same time, they also indicate the burden of the legacy. In the Western world, mourning rituals are lacking, the other side is not given space in everyday life. Ferdinand Dölberg's "Am Ende die Leerstelle" is a non-religious ritual: not only for the artist himself, but also for the viewers. The otherwise enclosed world of the mourners opens up, the pain finds its way into everyday life and in the process also becomes something hopeful: remembering quite literally gets a space, the presence of the absent in the still-present becomes concrete. A blank piece of paper is added to the portraits: Perhaps a farewell note that was never written? In the end, the space remains empty, the unsaid, the non-experienced, the inner monologue that remains addressed to the people who are no longer there. There is no resolution for grief - just as the life of the deceased remains incomplete. This also becomes clear in the sliding puzzle added to the portrait series: There are eleven variable parts and twelve gaps - so one gap always remains free. The system is reminiscent of the puzzle games children play when they are still at the age when they cover their eyes to hide. If you look closely, you can see a lying person. The viewers put the pieces together and create a person - a lost person. In puzzling as in mourning, it helps to relinquish control and to reflect on the narratives with which one can continue to live. Because the death of others always takes something from the living. The puzzle is never complete and thus always in motion. The French phrase "Tu me manques" expresses the loss in a nutshell: Unlike the German "Du fehlst mir", the Frech expression for "I miss you" also means that a part of yourself is missing. Indeed, just as those who are missing live on in those who are present, they also take a part of the living with them to the other side. Death is the ultimate cliffhanger, the end of authorship over one's own life - the story now continues to be written by the others. And there is something consoling in this, at least as long as those still present continue to tell the story as gently and carefully as they do in Ferdinand Dölberg's painting. There is a reason why funerals, just like exhibition openings, are also celebrations - eating and drinking are obligatory, laughing and crying are related emotions. In the end, faith remains, whatever its nature is. I remember once as a child having a picnic in the cemetery and being severely criticized by passing cemetery visitors for (quote) "irreverence" - a word I heard for the first time at that moment. I got out of the habit of picnicking in the cemetery after that - today I think it would be nice to reintroduce the ritual and thus to bring life to the place of death. Ferdinand Dölberg helps us to look at the other side (of the fence) and that is at least as hopeful as it is sad.

— Olga Hohmann

Selected works

Ferdinand Dölberg

Am Ende die Leerstelle

03.06. – 08.07.23

On Am Ende die Leerstelle

"La mort est du domaine de la foi" / "Death belongs to the domain of faith". - Jacques Lacan

On the other side Reflections on Ferdinand Dölberg's "In the End, the Empty Space“ by Olga Hohmann. "La mort est du domaine de la foi" / "Death belongs to the domain of faith". Jacques Lacan When little children want to hide, they cover their eyes. They think that if they cannot see what surrounds them, they would themselves also be invisible to their surrounding. At some point, the moment will come when they realize that they remain visible, even if they cannot see what they are surrounded by. When they want to hide, they now look for a place where they actually cannot be spotted - they no longer close their eyes to do so. Perhaps this happens at about the same time that they reach Lacan's mirror stage: they now recognize themselves in the mirror and at the same time misrecognize themselves, perceiving themselves as a subject, as a closed entity. When people grow old and prepare, very slowly, to pass away, they sometimes experience something similar to children covering their eyes so as not to be seen. I remember my grandfather repeating over and over again that he was afraid of his death because we, the relatives, would then also disappear. "If I am no longer there, then you are no longer there either" he repeated over and over again. So death was also a logic problem for him - he imagined it as an "other side" from which we who were alive would be just as invisible to him as he was to us. In Ferdinand Dölberg's exhibition "Am Ende die Leerstelle" ("At the End, the Empty Space"), death is quite literally negotiated as another side: The property of the artist's deceased father borders on a cemetery; only a fence separates the area of flourishing life, the garden, from that of death, the equally flourishing gravesites. A ladder leans against the fence, one can use it to dare a look at the other side or even climb over it. The view of the cemetery is also a view into one's (own) future. Only since he has changed sides, so to speak, does the artist use this ladder to pay his father a visit. In Ferdinand Dölberg's portrait series we see those who have remained on the other side - they almost seem like apparitions, as if they carry a part of the soul of their deceased loved ones with them. They hold objects in their hands, mundane artifacts left behind by the deceased: A chalice, an umbrella, a heat lamp, a hand truck, a bouquet of flowers. Sometimes they are ephemeral objects - they too become sacred without seeming specifically religious; one can draw conclusions about the characteristics of the people who have passed away. The mourners all have their own form of spirituality, one believes to recognize them in their sharp, serious look. One can impute to them melancholy and emptiness as well as serenity. Slightly larger than life, they look down on us, the viewers, evoking the presence of the deceased with their devotion to them, almost looking as if they themselves are in heaven or at least in a limbo between life and death, an approximation of that, unreachable other side. They have climbed the ladder to look, with an almost matter-offact gaze, over the fence where (invisibly) the dead lie. The figures seem deeper, more three-dimensional than their background, than the (virtual) space they are in, they remain black and white, out of time, their background is monochrome, like a deck of playing cards.

One almost thinks the portrayed are game characters or avatars - the game, the loss, is serious. As mourners, they find themselves in an interstice between one world and the other; with their memories, they themselves establish the presence of the ones who are absent, who also remain present in the objects left behind. The colorfulness gives the paintings something slightly nostalgic - nostalgia is a longing for a state that was never there, just as the memory of the deceased is always a displaced one, shaped by those who remember. Objects become shields against the helplessness of pain - at the same time, they also indicate the burden of the legacy. In the Western world, mourning rituals are lacking, the other side is not given space in everyday life. Ferdinand Dölberg's "Am Ende die Leerstelle" is a non-religious ritual: not only for the artist himself, but also for the viewers. The otherwise enclosed world of the mourners opens up, the pain finds its way into everyday life and in the process also becomes something hopeful: remembering quite literally gets a space, the presence of the absent in the still-present becomes concrete. A blank piece of paper is added to the portraits: Perhaps a farewell note that was never written? In the end, the space remains empty, the unsaid, the non-experienced, the inner monologue that remains addressed to the people who are no longer there. There is no resolution for grief - just as the life of the deceased remains incomplete. This also becomes clear in the sliding puzzle added to the portrait series: There are eleven variable parts and twelve gaps - so one gap always remains free. The system is reminiscent of the puzzle games children play when they are still at the age when they cover their eyes to hide. If you look closely, you can see a lying person. The viewers put the pieces together and create a person - a lost person. In puzzling as in mourning, it helps to relinquish control and to reflect on the narratives with which one can continue to live. Because the death of others always takes something from the living. The puzzle is never complete and thus always in motion. The French phrase "Tu me manques" expresses the loss in a nutshell: Unlike the German "Du fehlst mir", the Frech expression for "I miss you" also means that a part of yourself is missing. Indeed, just as those who are missing live on in those who are present, they also take a part of the living with them to the other side. Death is the ultimate cliffhanger, the end of authorship over one's own life - the story now continues to be written by the others. And there is something consoling in this, at least as long as those still present continue to tell the story as gently and carefully as they do in Ferdinand Dölberg's painting. There is a reason why funerals, just like exhibition openings, are also celebrations - eating and drinking are obligatory, laughing and crying are related emotions. In the end, faith remains, whatever its nature is. I remember once as a child having a picnic in the cemetery and being severely criticized by passing cemetery visitors for (quote) "irreverence" - a word I heard for the first time at that moment. I got out of the habit of picnicking in the cemetery after that - today I think it would be nice to reintroduce the ritual and thus to bring life to the place of death. Ferdinand Dölberg helps us to look at the other side (of the fence) and that is at least as hopeful as it is sad.

— Olga Hohmann

Selected works

Anton Janizewski Galerie,

Anton Janizewski Galerie,