Ferdinand Dölberg, Bahar Kaygusuz, Victor Payares, Noemi Pfister, Robin Rapp, Sophia Süßmilch, Emilia Urbanek, Georg Vierbuchen

A Slice of Landscape

On A Slice of Landscape

Oh wilderness, oh shelter from it“ (Elfriede Jelinek)

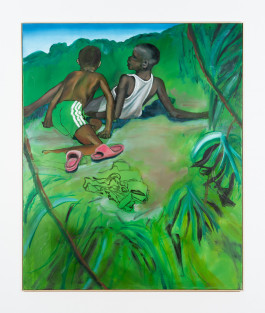

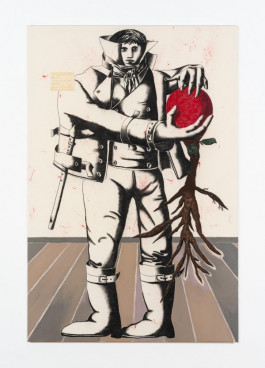

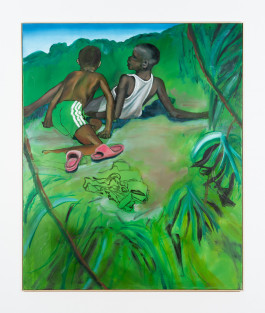

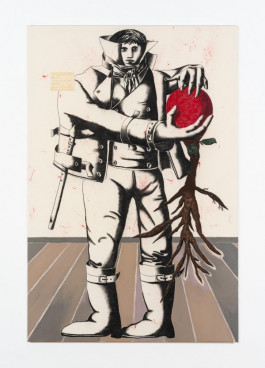

The concept of landscape presupposes that a "piece of nature" is selected and demarcated from the potential boundlessness of the "natural environment" - which, in turn, is to be perceived by the viewing subject as a kind of aesthetic wholeness. A landscape is thus something primordially limited, which, however, is not consciously perceived in its quality of being partial. The infinity of the real of nature, of wilderness, is terrifying - all the more important it is for urban beings to capture it exclusively in its imaginary limitedness, to tame it. There is a long tradition of landscape painting - and ever since the beginning of urban spaces, urbanites seem to have been attracted to capturing landscapes on canvas, sometimes en plain air. The mystical transfiguration of nature continues into the present with phenomena such as Cottage Core. Even in the face of climate change, a retreat into nature or a life involving its forces suddenly is particularly plausible and even necessary. The dichotomy of nature and culture seems to have been exhausted; nature can no longer be perceived as the other alone. In contemporary art, too, artists react to this downright invasion of forces not only in the form of the traditional attempt to tame them, to subdue them, but also in the affirmation of being overwhelmed by them. It is not only a longing for purity that is practiced here, on the contrary: artists become aware, in different ways, of the inseparability of the (painting) self from its environment. Above all, the practice of painting, in its materiality and physicality, supports the potential for becoming autonomous. In Emilia Urbanek's works, the bush stands as a metaphor for a part of the self and at the same time for a place to hide. As a potential place for coincidental and unexpected encounters. I planted my guts behind the house, they grew to be a glossy ass bush, sometimes I hide in it. Planting and domesticating the bush becomes an act of self-empowerment. The physicality of the plant is revealed, for example, in the almost carnal representation of the stems and leaves. The title „Vanitas incoming“ functions as a humorous art historical reference - skulls were traditionally depicted on so-called "vanitas" still lifes, symbolizing both "vanity" and the " ephemerality of earthly life." In Emilia Urbanek's work, however, the term "vanitas" becomes a symbol of constant change. Here, transience is above all a state of transition, also from the real to the not-yet-real. Noemi Pfister's work, on the other hand, represents an alternative - a parallel world in which the separation between human and nature has become fluid. We see a figure that moves between punk aesthetics and a mythical creature. In the otherworldliness of all elements, the depicted world borders on the fantastic. Nature is not perverted into a status symbol here - it is left free in its being so - the human a part of it. A utopia that plays with codes of the social present and thus does not seem to be so far away - but seems almost pioneering. In Robin Rapp's work "Petit frère" we see two figures, according to the title presumably brothers, who sit in a kind of forest clearing and seem to be observing something that remains invisible to the viewer of the work. The spectator is almost placed in a voyeuristic position, from which, as if hidden behind a bush, they observe the two children - who are absorbed by their own activity. A parallel world opens up that we don't quite understand, but the two protagonists seem certain of what they are doing; obliviously, they sit in the clearing. They wear clothes that one would assign to the state of leisure, maybe it's vacation time. They have taken off their shoes, adilettes, very casually, as if they expect to spend a while in the very position they are in at the moment. The artificially bright green of the shorts blurs with the plants surrounding them, which, in the mirror of the Adidas shorts, suddenly look just as artificial. It is unclear whether the scene has something harmonious or something threatening - the two children could also be in danger. Through the position that is assigned to one, that danger could also emanate from oneself, the voyeuristic viewer. In Bahar Kaygusuz's photographic works, the body becomes visible as a landscape - just as domestication methods of the natural emerge. On the one hand, a tree is shown as a body on which (plastic) surgery is performed, then again a haired torso becomes a green landscape. The body resists the control that is exercised over it; it can never be completely tamed, but always retains something wild, unruly. In the photograph of a crowded beach, one not only sees a seashore populated by half-naked people - a total body almost results from the individuals, the human being appears as a kind of (insect) plague or as a (bee) swarm, one associates the terms population growth and lack of resources. At the same time, however, the individuals are shown in their fragility, their slightly desperate desire for harmony and purity, and, again, their need for leisure, which only ever arises in relation to its opposite: Work. Sophia Süßmilch interchanges the (hierarchical) scales of people and plants by linking a plant with a naked body - the naked is about the size of a single leaf. It could both a weed-plague or a rare, valuable species of cactus; the depiction allows for both interpretations.

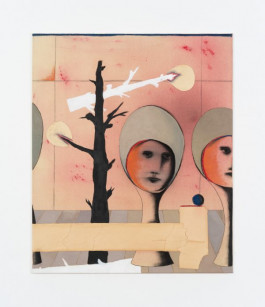

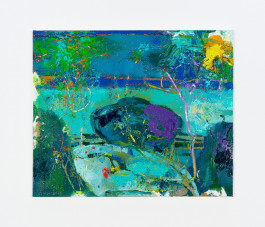

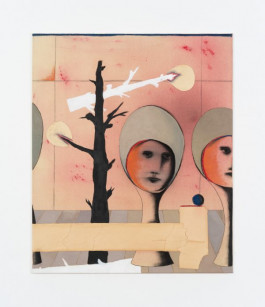

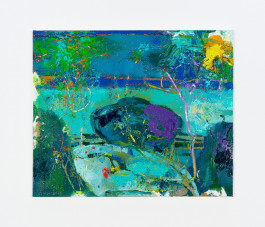

The human being appears here less as a foreign body than that it organically fits in. Gently and trustfully, the figure nestles its hairless head against the thorny stem and lets its legs blow in the wind or, as if under water, drift in the opposite direction. The feet are the same color as the petals, almost as if a transformation is taking place, a metamorphosis - the little human being is becoming floral. An animistic approach is also taken by Ferdinand Dölberg, in whose work faces literally appear at eye level with the tree top. It is unclear whether these are human trees, constructivist sculptures, or magnified street lamps. The moon faces themselves also have a thoroughly ambiguous expression: gentle, reassuring, but not necessarily cheerful, they look at us from their slightly out-of-place position - looking into the world in which they do not quite belong, but which they bathe in a pleasant (moon) light with their presence. Above them, a bare tree trunk is lit like a lighter. One of the two faces is shown only cut, one recognizes that the two figures are similar, but not alike - whether one perceives them as actual individuals or abstractions of the human is left to the viewer. Georg Vierbuchen uses discarded construction site warning lights, which he cuts in half and attaches to the image carrier in the form of a sun. The LED lamps, which are normally intended to delimit a territory, to mark it and for safety reasons to indicate that it cannot be entered, here become a force of nature themselves. The halved warning lights, as transformed ready-mades, are installed in the form of sunbeams - spreading their light on the image carrier and in the (gallery) space surrounding them. Their warm light, with which we associate both protection and threat, mixes with the cold light of the White Cube. It is both a conceptual and sensual approach that the artist takes here - the abstraction of the sun refers to an infantile understanding of the world, in which the unrepresentable of nature is put into a universalizable form: The sky and water blue, the clouds white and clearly outlined, the sun placed in the upper right corner, four defined rays of sunlight emanating from it. The treatment of non-disposable material, the ruins of civilization, is also present in Georg Vierbuchen's work - art here becomes a refuge for the objects left behind, a renaturalization of the artificial. Victor Payare's painting represents the very reality of nature, of which most people are afraid and which for centuries has been supposed to be tamed (by painting). We no longer see a "slice of landscape", we see the whole, sublime brutality of it, in its terrifying beauty. The limits of language, or of what can be grasped, named, and classified, are revealed and transcended - taxonomy and lexicality disintegrate, leaving a contradictory but poetic dimension. Employing a strategy of unlearning, Payares manages to confront us with the unrepresentable. It is a loving, almost sentimental look at the potential violence of nature. The viewing subject blurs with its surroundings - something breaks (as an event) over the viewing subject and makes complete distance impossible. Nature is sublime to the observer. Perhaps this is also what is to be triggered by the escape from the city - an escape from the world that expresses not only a privileged enjoyment, consumption, and a longing for purity, Cottage Core, but also a desire for transgression - the abysmal is to be affirmed, nature is not only to be tamed, put in its place, but the human being itself is to be revealed in its limitedness. We are not apart from it, we are part of it, whether we like it or not. No frame, lense or canvas can change that. The medium of painting remains perplexed in the best sense - and the works thus inexhaustible. Underlying all the positions is a certain romanticism as well as a terror, a radical longing as well as a cautious, loving fear - something tentative that slowly blossoms, in different directions. In the attempt to capture something that eludes our concepts and our perception, all artists produce in their own way something unfathomable, enigmatic, mysterious - something that eludes us, that withdraws, just like nature itself. Painting becomes a piece of nature, a slice of landscape. Or even more: Not only a slice, but the whole cake. It transcends the boundaries of the canvas and radiates onto us, the viewers, incorporating us just as we incorporate it. - Olga Hohmann

Selected works

Exhibition views

Ferdinand Dölberg, Bahar Kaygusuz, Victor Payares, Noemi Pfister, Robin Rapp, Sophia Süßmilch, Emilia Urbanek, Georg Vierbuchen

A Slice of Landscape

On A Slice of Landscape

The concept of landscape presupposes that a "piece of nature" is selected and demarcated from the potential boundlessness of the "natural environment" - which, in turn, is to be perceived by the viewing subject as a kind of aesthetic wholeness. A landscape is thus something primordially limited, which, however, is not consciously perceived in its quality of being partial. The infinity of the real of nature, of wilderness, is terrifying - all the more important it is for urban beings to capture it exclusively in its imaginary limitedness, to tame it. There is a long tradition of landscape painting - and ever since the beginning of urban spaces, urbanites seem to have been attracted to capturing landscapes on canvas, sometimes en plain air. The mystical transfiguration of nature continues into the present with phenomena such as Cottage Core. Even in the face of climate change, a retreat into nature or a life involving its forces suddenly is particularly plausible and even necessary. The dichotomy of nature and culture seems to have been exhausted; nature can no longer be perceived as the other alone. In contemporary art, too, artists react to this downright invasion of forces not only in the form of the traditional attempt to tame them, to subdue them, but also in the affirmation of being overwhelmed by them. It is not only a longing for purity that is practiced here, on the contrary: artists become aware, in different ways, of the inseparability of the (painting) self from its environment. Above all, the practice of painting, in its materiality and physicality, supports the potential for becoming autonomous. In Emilia Urbanek's works, the bush stands as a metaphor for a part of the self and at the same time for a place to hide. As a potential place for coincidental and unexpected encounters. I planted my guts behind the house, they grew to be a glossy ass bush, sometimes I hide in it. Planting and domesticating the bush becomes an act of self-empowerment. The physicality of the plant is revealed, for example, in the almost carnal representation of the stems and leaves. The title „Vanitas incoming“ functions as a humorous art historical reference - skulls were traditionally depicted on so-called "vanitas" still lifes, symbolizing both "vanity" and the " ephemerality of earthly life." In Emilia Urbanek's work, however, the term "vanitas" becomes a symbol of constant change. Here, transience is above all a state of transition, also from the real to the not-yet-real. Noemi Pfister's work, on the other hand, represents an alternative - a parallel world in which the separation between human and nature has become fluid. We see a figure that moves between punk aesthetics and a mythical creature. In the otherworldliness of all elements, the depicted world borders on the fantastic. Nature is not perverted into a status symbol here - it is left free in its being so - the human a part of it. A utopia that plays with codes of the social present and thus does not seem to be so far away - but seems almost pioneering. In Robin Rapp's work "Petit frère" we see two figures, according to the title presumably brothers, who sit in a kind of forest clearing and seem to be observing something that remains invisible to the viewer of the work. The spectator is almost placed in a voyeuristic position, from which, as if hidden behind a bush, they observe the two children - who are absorbed by their own activity. A parallel world opens up that we don't quite understand, but the two protagonists seem certain of what they are doing; obliviously, they sit in the clearing. They wear clothes that one would assign to the state of leisure, maybe it's vacation time. They have taken off their shoes, adilettes, very casually, as if they expect to spend a while in the very position they are in at the moment. The artificially bright green of the shorts blurs with the plants surrounding them, which, in the mirror of the Adidas shorts, suddenly look just as artificial. It is unclear whether the scene has something harmonious or something threatening - the two children could also be in danger. Through the position that is assigned to one, that danger could also emanate from oneself, the voyeuristic viewer. In Bahar Kaygusuz's photographic works, the body becomes visible as a landscape - just as domestication methods of the natural emerge. On the one hand, a tree is shown as a body on which (plastic) surgery is performed, then again a haired torso becomes a green landscape. The body resists the control that is exercised over it; it can never be completely tamed, but always retains something wild, unruly. In the photograph of a crowded beach, one not only sees a seashore populated by half-naked people - a total body almost results from the individuals, the human being appears as a kind of (insect) plague or as a (bee) swarm, one associates the terms population growth and lack of resources. At the same time, however, the individuals are shown in their fragility, their slightly desperate desire for harmony and purity, and, again, their need for leisure, which only ever arises in relation to its opposite: Work. Sophia Süßmilch interchanges the (hierarchical) scales of people and plants by linking a plant with a naked body - the naked is about the size of a single leaf. It could both a weed-plague or a rare, valuable species of cactus; the depiction allows for both interpretations.

Selected works